All regions of the body are vulnerable to a unique set of injuries, depending on how the structures in that particular area are affected by common activities. The likelihood of injury therefore varies from one location to the next, with higher activity levels generally corresponding with a greater injury risk throughout the entire body. But there are also certain âhotspotsâ that tend to be involved in injury far more frequently than others.

One of these hotspot areas is the feet and ankles, which often sustain damage because of the heavy loads they have to withstand from the rest of the body. There are several structures and mechanisms in place that increase their durability and prepare them for these forces, but like every other body part, they have a breaking point. When pushed past this point, the result is often a wide range of potential injuries.

Below are some of the most common injuries that occur in the feet and ankles:

- Ankle sprain: ankle sprains occur when the ligaments surrounding the ankle are stretched beyond their limit in a forceful motion; these are the most common injuries in all of sports, and about half of all ankle sprains are related to physical activity; nearly 25,000 people sprain their ankle every day, and they typically lead to pain, swelling, and an inability to put pressure on the ankle

- Plantar fasciitis: generally considered to be the most common cause of heel pain in adults, this condition results from inflammation of the plantar fascia; when this tissue is overstrained from repeated activityâlike runningâit becomes inflamed, which leads to a stabbing pain near the heel that is most noticeable upon waking up

- Achilles tendinitis: another overuse injury due to inflammation of the Achilles tendon; itâs most common in runners who do lots of speed training, uphill running, or rapidly increase their training intensity or duration, and it leads to heel pain that usually comes on gradually as a mild ache in the back of the leg or above the heel

- Stress fractures: these injuries are the result of small cracks or severe bruising caused by repetitive strain to the foot; they are common in both children and adults, and are most frequently seen when a person changes their usual exercise regimen with a sudden increase of activity or a change in workout surface

- Turf toe: this is a sprain of the ligaments surrounding the big toe when itâs bent back too far (hyperextended), which is common in football players; it can occur from a sudden, forceful movement or repeated hyperextensions over a period of time, and leads to pain, swelling, and limited movement of the big toe

- Severâs disease: this is an overuse injury that results from inflammation of the growth plate (an area of growing tissue near the ends of bones in children) in the heel; itâs caused by repetitive stress to the heel and typically occurs during growth spurts; symptoms include pain and tenderness underneath the heel. Be sure to read our newsletter next week for some useful exercises that will help you maintain mobility and reduce your risk for foot and ankle injuries.

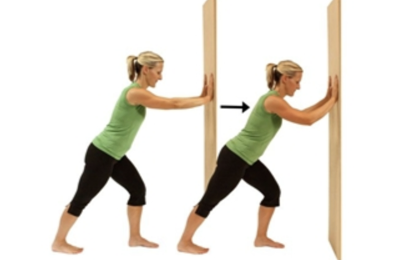

Be sure to read our newsletter next week for some useful exercises that will help you maintain mobility and reduce your risk for foot and ankle injuries.