In our last newsletter, we explained why knee pain is so common and explored some of the most common conditions that involve the knee. Knee pain can strike at any age, and while the specific reasons it occurs may vary among different populations, the result is usually the same: an inability to move and function normally in daily life.

We need healthy knees to perform just about any activity that involves the legs, which means the ability to walk, squat, or sit/stand from a chair can be impaired by knee pain. Many of these activities are vital to get through a typical day, meaning that knee pain can prove to be a major hindrance to one’s quality of life. For athletes, knee issues can cause further complications by limiting or preventing play entirely until the pain resolves.

One of the main reasons knee pain occurs so frequently is an overall lack of mobility in the joint, which is often due to inactivity. The good news is that you can improve your knee mobility and reduce your risk for knee pain in the process by performing exercises that target the muscles surrounding the knee. We recommend the following:

Four mobility exercises to reduce your risk for knee pain

Disclaimer – This article and associated images is for educational purposes only. They are not meant to be a substitute for physical therapy or medical care. Please consult with your physical therapist and/or doctor before you start this or any other exercise program.

- Quadriceps stretch

- Lie on the floor on one side

- Grasp your ankle and gently pull your heel up and back until you feel a stretch in the front of your thigh

- Tighten your stomach muscles to prevent your stomach from sagging outward, and keep your knees close together

- Hold for about 30 seconds

- Switch legs and repeat

- Hamstring stretch

- Lie on the floor near the outer corner of a wall or a door frame

- Raise your left leg and rest your left heel against the wall

- Keep your left knee slightly bent

- Gently straighten your left leg until you feel a stretch along the back of your left thigh

- Hold for about 30 seconds

- Switch legs and repeat

- As your flexibility increases, maximize the stretch by gradually scooting yourself closer to the wall or door frame.

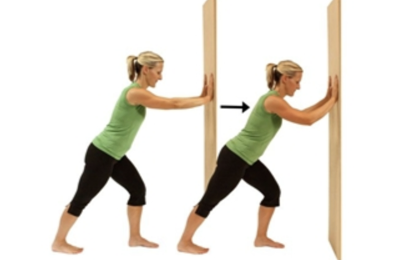

- Calf stretch

- Stand at arm's length from a wall or a piece of sturdy exercise equipment

- Place your right foot behind your left foot about a foot away

- Slowly bend your left leg forward, keeping your right knee straight and your right heel on the floor

- Hold your back straight and your hips forward

- Don't rotate your feet inward or outward

- Hold for about 30 seconds

- Switch legs and repeat

- To deepen the stretch, slightly bend your right knee as you bend your left leg forward

- Knee range of motion exercise

- Sit down with both legs out in front of you

- Place a towel around your ankle and hold it with both hands

- Pull the towel and slide your ankle towards your buttocks while keeping your heel on the ground

- Continue pulling the towel as far as your knee can bend

- Hold for about 30 seconds

- Slide your ankle back to the starting position

- Switch legs and repeat

A physical therapist can help ensure that you’re performing these exercises correctly and provide you with additional exercises to further increase your knee mobility. Contact us today to learn more or schedule an appointment.

In our next newsletter, we’ll discuss the role that strengthening exercises can play in alleviating your knee pain.